What 70s Punks Can Teach Us About Fighting Fascism

This week, London art centre Rich Mix is partnering with Love Music Hate Racism to make ‘White Riot’ available to rent via their website until the 16th of August, with a free live online Q&A taking place at 19:00 BST on Thursday 13th August.

Rent the film and book yourself a place in the Q&A here.

From director Rubika Shah comes a raucous, energetic film detailing the extraordinary journey of Rock Against Racism (RAR), a British musical collective that channeled anti-fascist sentiments into a flourishing cultural project.

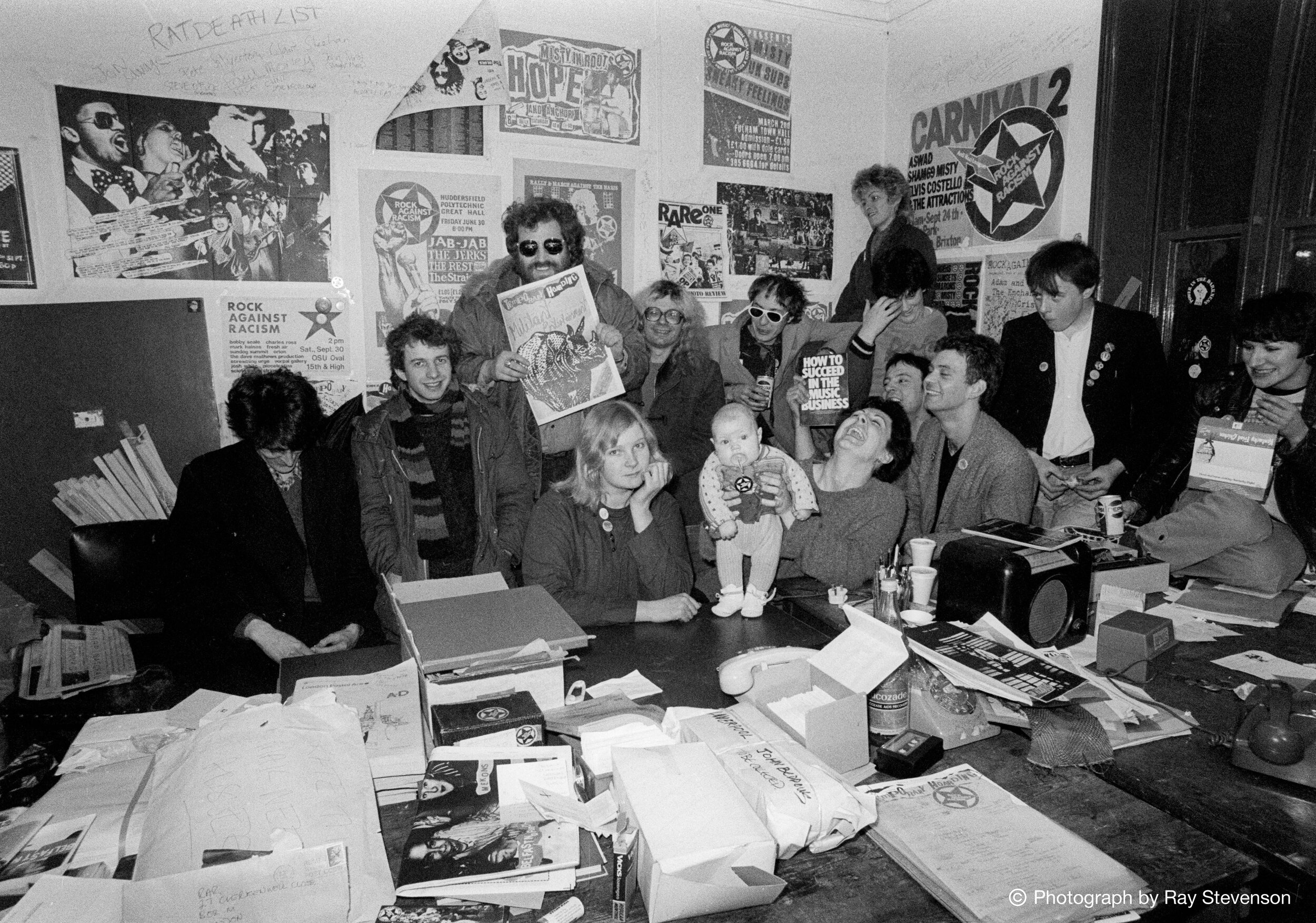

Best Documentary winner of BFI London Film Festival 2019, White Riot makes extensive use of stunning archival footage from the late 1970s illustrating, in both bright colour and grainy black and white, the turbulent political climate of the time. Shah successfully creates a DIY, fanzine aesthetic, presenting photographs and footage with hand-drawn annotations, illustrations on filmstrips, or alongside newspaper cuttings. These touches weave a passionate tale of uprisings and street fights so intimately that we feel as though we were there when they happened, or perhaps wish we had been.

White Riot tells of a battle fought underground - political messages and demonstrations against the far-right National Front (NF) were promoted through zines, art, posters and, of course, gigs. The film deftly showcases music’s unifying force and its vitality as a vehicle for change in a culture war. As RAR founder Red Saunders explains, this was exemplified by the huge anti-racist carnival in Victoria Park in 1978, which succeeded beyond the organisation’s wildest dreams. A sea of music, colours, noise, signs, and cultures were on display in the march from Trafalgar Square to the, eventually mobbed, stage. The influence and energy of music is apparent, but the emphasis is on where to direct that built-up anger.

Though backed by a fittingly rockin’ soundtrack, White Riot is much more political than it is musical, tracking the NF’s roots to Oswald Mosley’s blackshirts, charting its rise and depicting the violence of their language and actions in the 1970s. Though many will be familiar with the NF as a white supremacist/Neo-Nazi organisation, what is particularly disconcerting is seeing footage of their supporters: young, fresh-faced, working-class, often punks or part of other popular subcultures of the time. Regular people, as the film articulates, recruited in the streets or even outside schools. This is an evergreen message to take away from White Riot: when organised, the far-right message resonates with people, particularly the disaffected or alienated. Over time, the roots of racism have remained much the same - lack of opportunities and scapegoating those with the least power for capitalism’s economic failures.

Credit: Ray Stevenson

As RAR grew, with massive acts like The Clash carrying their message, the stakes of opposing bigotry became higher. The personal, often very emotional footage on display brings to reality what RAR was rallying against. More than just a chance to share music, it was an opportunity to confront a very active and violent racism. This violence ranged from vandalism and intimidation, to death threats and firebombing, and should in no way be understated. It really was a life or death situation for those swept up in this nationalist, anti-immigration fervor. As Saunders articulates, ‘‘We peeled away the Union Jack to reveal the swastika’.

We see Shah’s narrative recurring in today’s political climate: right-wing press fanning the flames of racism, the politics of fear, police brutality and the harassment of black people. Indeed, the NF made their support for the police clear, citing their protection in marches and even claiming many in the force were secretly (or not so secretly) sympathetic to their cause. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and a resurgent far-right, this film is as prescient as ever. White Riot ends with a fitting warning about what is to come next, how the street battles of the 1970s have been repeated since and will be repeated again in different forms. In this sense, the history of RAR can almost serve as a blueprint for a much-needed cultural alternative to tackling fascism.

Credit: Syd Shelton

Rather than focusing on the gloomy realisation that history is repeating itself, the film’s message of reaching across communities resonates to a far greater degree. At its most uplifting, we see the masses of letters written to RAR pledging support, agreeing to tackle racism, asking for leaflets, badges and, vitally, setting up RAR organisations in their own area, from Aberystwyth to Aberdeen. This widespread enthusiasm and participation cemented the remarkable legacy of RAR.

The success of RAR’s concert in East London and the National Front’s subsequent decline speaks to how ordinary people can change the world. White Riot is a creative and informative illustration of this, and we must consider how to further build on this message, especially now.

This week, London art centre Rich Mix is partnering with Love Music Hate Racism to make ‘White Riot’ available to rent via their website until the 16th of August, with a free live online Q&A taking place at 19:00 BST on Thursday 13th August.

Rent the film and book yourself a place in the Q&A here.